Finally Home

“Preciosa serás sin bandera

Sin lauros, ni gloria

Preciosa, Preciosa

Te llaman los hijos de la libertad.”

—Rafael Hernandez

On a hot, sunny afternoon, the week of July 22, 2019 I finally felt at home.

I was standing on the corner in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico, behind a barricade, in front of La Fortaleza — the Governor’s mansion. The crowd and I were singing Marc Anthony’s rendition of Preciosa, one of our most treasured anthems. My heart overflowed as I celebrated the community organizing victory that was activated by youth and public figures via social media that summer. Tears fell down my cheeks as I sang the song we all know.

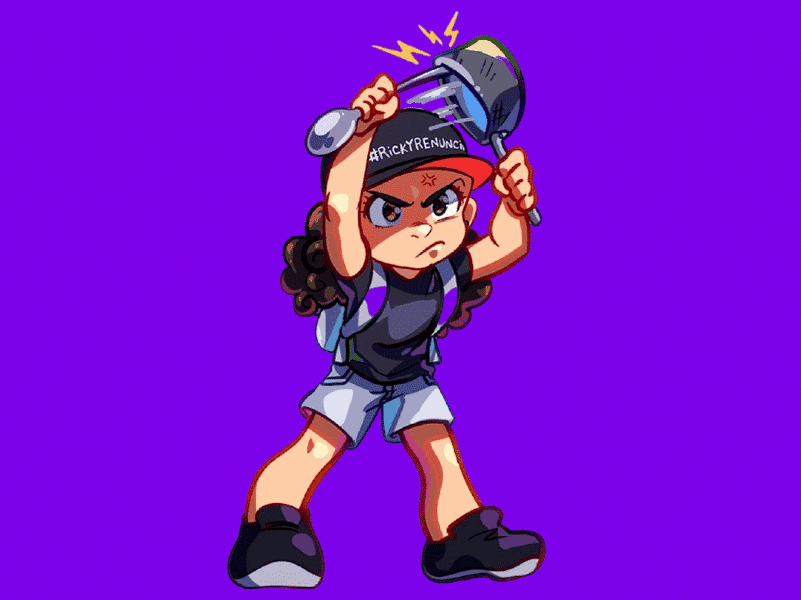

During these protests in Puerto Rico, Cacerola[1] girl was captured in what became a viral sensation on Twitter. She’s one of my sheroes. Someone created this cartoon-like meme of her on social media. She expressed her fury using a pot and a cooking spoon. When she found herself surrounded by police officers towering over her wearing riot gear, she kept her head held high and continued to exercise her constitutional right to free speech, asking why the police were so scared of little old her.

She stood her ground. She used everything she had. She used her time, her words, her hands, body and voice. To this day, #CacerolaGirl has managed to remain anonymous. Any interviews she has done have been under condition of anonymity. She chose to lead from the front as part of a collective.

Everyday people in Puerto Rico were slowly recovering from an unimaginable series of soul-crushing events. Greedy bankers sold eager politicians a bill of goods that resulted in the island owing billions to Wall Street. Since U.S. law prohibits Puerto Rico from declaring bankruptcy (only the U.S. Congress can do this) a non-elected fiscal oversight board began instituting ruthless cost-saving measures — cutting abuela’s pension to pay interest to Wall Street vulture capitalists. If that were not enough, the largest hurricane in 100 years led to the longest power outage in United States history. My family members, like many others, washed laundry in the rain, instead of using their own washing machines. Meanwhile the corrupt Puerto Rico Governor conspired with the U.S. to hide the fact that 4,465 people died as a result of Hurricanes Irma and Maria in an effort to limit emergency relief funds to the island colony.

While people were suffering from cuts and life-threatening power outages, elected leaders privately poked fun at their suffering — betraying public trust. They closed schools with impunity, embezzled money, dealt profitable contracts to themselves and laughed about it in private chats. When their private chats went public, the entire island responded with sustained public protests until the corrupt Governor was forced to resign mid-term. That’s what was happening that day I found myself on Calle de la Fortaleza, which had been renamed by the protest leaders to Calle de la Resistencia.

One of the many chants during the rebellion in Puerto Rico was “¡Somos más y no tenemos miedo!” (There are more of us, and we are not afraid). The revelation of the private chat conversations were an unimaginable falta de respeto.

What happened in Puerto Rico, reminds me of the insidious attempts to take away the right to vote from people in Georgia over many years. Voter suppression, like private chats, look much worse when they see the light of day. Nse Ufot, the political mastermind leading the New Georgia Project says it much more clearly. “When you turn on the lights, the cockroaches scatter.”

The November, 2020 election in the U.S. broke all records. Over 150 million people used their voice and voted. These events in Puerto Rico and the United States have shown the world what happens when political ‘slack’ gets activated. This is power that people have, but don’t choose to use regularly. Atabex Garcia, a student who marched through the rain during the national day of protest told me she got emotional when she saw live video of Puerto Ricans in New York’s Grand Central Station dancing and singing, “Yo soy Boricua, pa’ que tu lo sepas,” I’m sure that morning when she laced up her sneakers for her first-ever protest, she had no idea how many people had her back.

The moment brought people together across political parties, economic status, the island and the diaspora—those who have left Puerto Rico over the years. A bit of the latent power we’ve always had was used – for a moment. In his classic political and economic analysis titled, “Exit, Loyalty and Voice,” Albert O. Hirschman writes:

“The discovery that citizens do not normally use more than a fraction of their political resources originally came as a surprise and disappointment to political scientists who had been brought up to believe that democracy requires for its functioning the fullest possible participation of all citizens.”[2]

The protests and strikes in Puerto Rico have taught the world a lesson in democracy. They have changed Puerto Rico. And, they have changed me.

In July, 2020, one year after that day I stood on the San Juan street corner, I moved home to Puerto Rico. It is an understatement to say that 2020 was a clarifying year for all of us. It was the year of COVID 19, Ahmad Arbery, Breonna Taylor, the public lynching of George Floyd and so many others. Four generations ago, my Abuelita Goyita Miranda was kicked off her land and left homeless and destitute with 6 daughters when her husband died. When COVID hit and I thought about where I truly wanted to be, it was here. I’ve come back to reclaim some of what was lost.

A few weeks after I arrived, I was talking with to a group of Boricua sisters and I told them why I moved back. One woman responded, “Welcome home!” Her words melted something frozen deep in my soul as warm tears emerged. Danaliz Dávila, a community organizer here in Puerto Rico shared some wisdom with me about the island and the mainland in the days to come. She said the U.S. response to the hurricane was so paltry that, “Si no hubiera sido por la diaspora, hubieramos comido fango.” (If it hadn’t been for the diaspora, we would have eaten mud). As a Puerto Rican woman who was born and raised on the mainland U.S., I’ve always felt one step removed from the island.

Not anymore. Puerto Rico is my home.

Home.

Warm welcomes from family you haven’t seen in years.

Home.

The smell of sofrito when you walk down the street.

Home.

Women with meat on their bones and a twist in their step.

Home.

Parqueando to grab un sandwich for breakfast.

Home.

A steady ocean breeze, impatient drivers, revolúces, coquíes and wild horses running down the road.

Home.

Finally found.

[1] Cacerola girl = cooking pot girl

[2] Hirschman, Albert O., Exit, Loyalty, and Voice, page 14.